Bunkergeil

In Trier, a landmark case is underway in which prosecutors, for the first time in Germany history, are trying to convict the administrators of a hosting company for crimes committed using their infrastructure. An exclusive report from the courtroom.

Me at the trial at Landgericht Trier, photo by Mario Zender (WochenSpiegel)

On Monday, unprecedented legal proceedings kicked off in the picturesque western-German town of Trier on the river Moselle. Authorities are planning a gigantic trial that is expected to take until the end of 2021. State prosecutors are suing eight defendants, who they are charging with having been accessory to over 250,000 crimes. According to the prosecutors, these defendants ran one of the biggest hosting operations for illegal websites in the world – and did so knowingly. The case marks the first time in German legal history that a hosting provider is facing criminal proceedings for the websites it hosted. It will be crucial for prosecutors to prove that the defendants knew what was hosted on their server – and willingly cooperated with criminals – or the whole case will fall apart and could prove a disaster for similar criminal investigations in the future.

I was in Trier on Monday and will be reporting on this lawsuit for Europe’s biggest IT magazine c’t as well as Germany’s premier tech news site heise online. Since I currently have no clients who want me to cover this trial in English, but I nonetheless think it is important that English-speaking audiences get first hand reporting on this, I will be providing English-speaking coverage here on my blog.

The hosting company in question is called CyberBunker and was being operated out of an Cold War era military bunker in the tiny town of Traben-Trarbach on the Moselle, about an hour by car north-east of Trier. According to the prosecutors, the self-proclaimed “bullet-proof hoster” was operated by the main defendant Mr. X with help from his two sons X.O., Y.O. and his previous partner Mrs. B – all co-defendants in the case. Another man, Mr. R., was first employed as a hired help, but quickly got promoted to become assistant manager to X., even acting as his proxy when he wasn’t around. The other three defendants where employed as admins and programmers to keep the infrastructure of the hosting company running. One of the admins, Mr. J., was an adolescent who was first hired as an intern and then stayed on at the bunker. Since he wasn’t legally of age while the alleged crimes were being committed – defendant Y.O. was also underage some of the time he worked for his father – the case is being tried in front of the Große Jugendkammer at the Landgericht Trier, with lay judges and other court officials qualified to judge criminal cases where minors are involved.

The CyberBunker Republic

X is relatively well known among investigative journalists and IT security researchers who deal with underground marketplaces and shady service providers involved in the sale of drugs, malware and DDOS services. Him and a friend and colleague – who has not been indicted in the current proceedings, even though his hacker alias turns up in a domain connected to the hosting company and which linked to child pornography – set up the hosting company CyberBunker in the Netherlands in the mid-90’s. Both men are Dutch and when X. bought an old 60’s military bunker near the town of Goes in the Dutch province of Zeeland, they developed the idea to convert it into a nuclear-proof hosting company. X. set up a non-profit foundation, apparently financed by money he had accrued from running a chain of personal computer stores, to buy the bunker. Reportedly, both men were driven by an idea that was very prevalent in the early days of the internet: Cyberspace as a sovereign realm that is independent of nation states and their meddlesome executive organs. They even proclaimed CyberBunker to be a sovereign republic. X. now proclaims this to have been a joke, but his business partner still seems attached to the idealistic roots of the company even today.

The first CyberBunker in the Netherlands partly burned out in 2002. It took several days to extinguish the flames and when investigators could enter the structure, they discovered the source of the fire had been an illegal drug lab that was apparently producing the synthetic drug ecstasy when the fire broke out. To cover the enormous operating costs associated with running the nuclear bunker, X. had rented out part of it to another group. The drug lab was located in this area of the bunker. X, who reportedly suffered burns to his hands and face in the fire and was rushed to a hospital, maintained he didn’t know anything about the drug lab run by his sub-letters. X. wasn’t charged by the Dutch authorities, but his business license was taken away. There were a few civil lawsuits and he eventually was able to return to run his hosting company. In the meantime, the CyberBunker servers were migrated to more conservative datacentres in Amsterdam.

The first CyberBunker location in Kloetinge, near Goes, in the Dutch province of Zeeland (Image: Google Maps)

Pretty soon, X set out to look for another bunker to convert into a server farm. According to a feature on him and his company in the New Yorker, former associates of X. have described him as “bunkergeil” – a German neologism that can be translated as “horny for bunkers”. According to that story, X. can’t say why he likes bunkers; just that he likes them very much. He prefers to work and live underground. Because of what happened to the first CyberBunker in Zeeland, X. apparently recognised that it would probably be unlikely for the Dutch government to sell him another bunker and decided to look at Germany’s many bunker complexes. Because of its strategic location during the Cold War, Germany is littered with old nuclear bunkers built by NATO and occasionally the military decides it doesn’t need one of them anymore. This happened in Traben-Trarbach, where an old nuclear bunker complex used by the German military to predict weather conditions in operational theatres for the German army went on sale in 2012. In the same year, X.’s foundation proposed to buy it. He gave a presentation during a closed meeting of the town’s council promising to convert the bunker into a state-of-the-art data centre used by the largest international corporations. He also promised hundreds of jobs for the townspeople whose economy got hit extremely hard when the military left. There’s nothing in Traben-Trarbach except vineyards, the bunker and a medium-sized tourism industry.

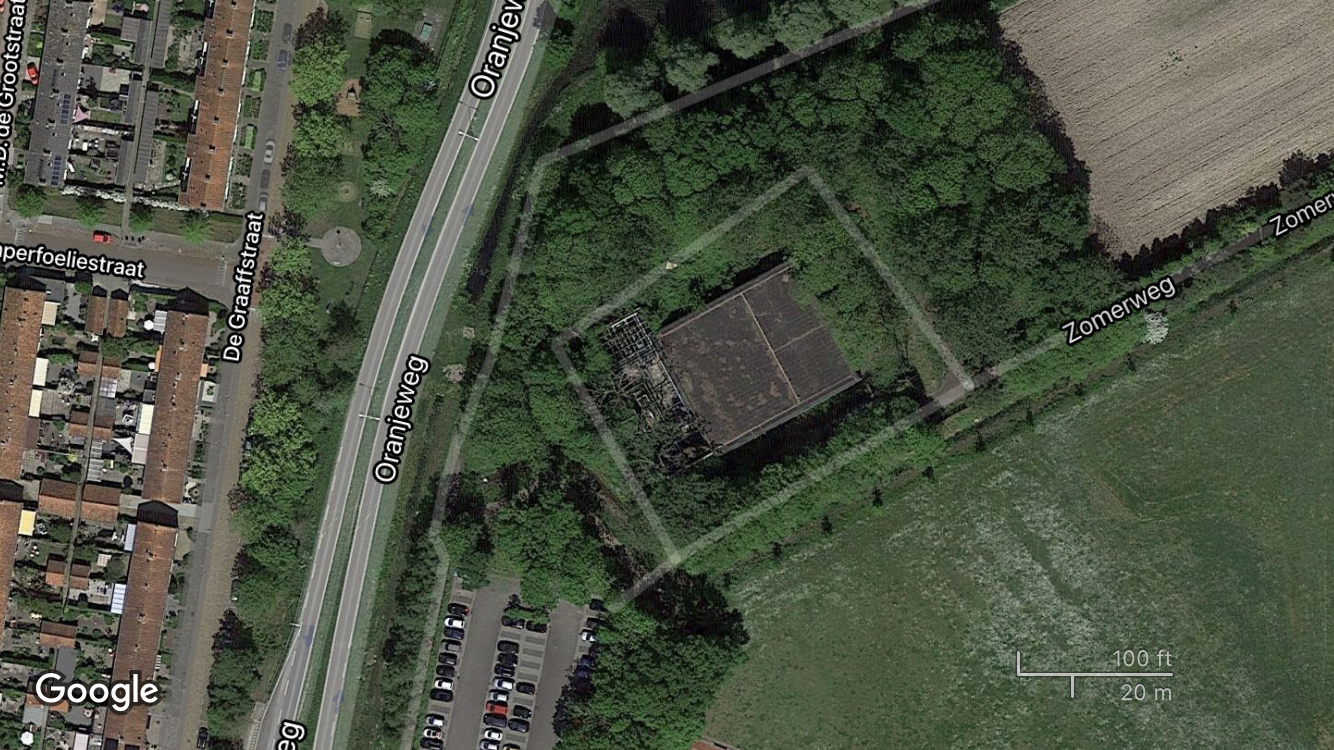

The new CyberBunker location on Mont Royal above Traben-Trarbach in Germany (Image: Google Maps)

Several people on the council apparently had bad feelings about X. and is foundation. According to a story in Der Spiegel the mayor at the time did some research and came across stories about the first bunker, the fire and the ecstasy lab. He forwarded this to the criminal police of the federal state of Rhineland-Palatinate, which would be responsible to investigate such things. The police, in turn, informed the federal real estate authority which was selling the bunker. But since nobody was willing to buy the bunker at the asking price of €450,000 (not to mention spending the money and manpower necessary to maintain the bunker complex), the authorities decided to approve the sale to X.’s foundation in the Netherlands. After the sale was finalised, X. moved into the bunker in June of 2013 and began to convert it into a datacentre with the help of his two sons. The facility reportedly became operational in 2014. According to the prosecutors in the case now being brought in Trier, it cost a total of €750,000 to buy and convert the bunker into a hosting location. Part of the cost was a new highspeed fibre connection that X. had put in to connect his servers to the major internet hub roughly 100km to the east in Frankfurt. When the indictment was read out on Monday, one of the points the prosecutors made was that an investment of €750,000 to build a hosting company the size of CyberBunker 2.0 would have been foolish had X. and his colleagues not intended on making money off criminals who could pay the overpriced hosting fees they commanded.

Prosecutors and criminal investigators apparently took only a cursory glance when X. and his company set up shop in Traben-Trarbach. Looking at the company’s website, it seemed clear that they were advertising to criminals, Oberstaatsanwalt Jörg Angerer (the chief state prosecutor in the case) is quoted as having said in the New Yorker story. But knowing that is one thing, going after the hosting company itself instead of the admins of the criminal websites in question is quite another. This is because Germany has a kind of safe harbour provision when it comes to internet service providers. Rooted in laws made for similar situations in the analogue world, the established case law roughly goes as follows: As long as an internet service provider does not know what its clients are up to, the company is not responsible for any crimes that are being perpetrated using their infrastructure. With other words: If they host an underground drug marketplace but don’t know about it, the people running the forum and the buyers can be prosecuted for crimes, but the people the servers are rented from can’t be. But as soon as somebody complains to the provider, they need to take action: Take the servers in question down and cooperate fully with police investigations into their clients. And because this happens a lot, that’s where bullet-proof hosters come in – companies who do not follow these rules and protect their clients and their websites from intrusions by the state. Usually, these companies host their servers in countries were investigators can be bribed or where the state is busy with other, more pressing problems – eastern Ukraine for example. Because it seemed quite hard to prove that the CyberBunker people knew of the illegal sites that were almost certainly being hosted on their servers, the prosecutors decided to not go forward with an investigation in 2013.

Enter The Penguin

This changed in November of 2015 when Nicola Tallant, an investigative reporter with the Irish tabloid Sunday World, tracked down an Irish mobster known as The Penguin in Traben-Trarbach. In the picture Tallant’s photographer took in front of a restaurant in the small German town, The Penguin (who at that time went by the alias Mr. Green) can be seen walking next to X. and his son X.O. At that time, the mobster was apparently hiding out with the CyberBunker crew, meeting them regularly for breakfast and lunch in various restaurants. The Sunday World seems to have been tipped off to Mr. Green’s presence at the bunker by one of the young interns working there. According to another piece Tallant published in May of this year, the Irish mob boss, who specialises in importing drugs to Ireland (often via the Netherlands), knew X. from time spent in Amsterdam and had helped finance the CyberBunker in Traben-Trarbach. When Angerer and his colleagues got wind of the sighting of a major organised crime figure in Traben-Trarbach, obviously connected to the hosting company in the bunker, they grew very alarmed. This was the moment when, according to Der Spiegel, they decided to start a full investigation into the CyberBunker and everyone connected to it. They used the drug boss’s presence to convince a judge to allow them to tap the Irishman’s phones (he used 16 different devices at the same time) and the phones of everyone in the bunker. Tracking devices were attached to their cars, everyone was being followed. Investigators also tapped the hosting operation’s internet connections. The bunker and its inhabitants were placed under intense surveillance.

Der Spiegel says that prosecutors allege that Mr. Green, the mobster, who has spent time in jail in both Ireland and the Netherlands, is the real head of what amounts to a criminal organisation that ran the datacentre in the bunker. They are charging the eight defendants in the Trier case with belonging to this criminal organisation, an offense that could result in a fifteen year prison sentence. The two defendants who allegedly committed crimes fully or partially while still being minors would probably receive sharply reduced sentences. But while the operators of the hosting service are being charged, the apparent criminal mastermind has neither been indicted nor arrested. In the end, the prosecutors seem to have been unable to definitely tie Mr. Green – who is said to have spent up to €700,000 helping to finance the bunker operation and allegedly gave the orders around the place – to the crew in Traben-Trarbach. They either couldn’t make the connection stick, could not prove his involvement in criminal activity (he apparently always employed a plethora of codewords when using unencrypted connections) or were unwilling to compromise their investigation by arresting the mob boss. The last time he was sighted visiting the bunker was in 2017.

Green is reported to not only having been interested in the hosting of illegal websites, for which he is alleged to have provided X. with ample connections in the criminal underworld of drug smugglers and cartels. He apparently also used X. as a kind of technological advisor. And collaborated with him in the design of several encrypted communication apps that were installed on customised Blackberry and Android smartphones. Tallant maintains that this was a sort of retirement plan for the Irish mobster: To move some of his drug money into a business that was at least semi-legal. As the theory goes, he wanted to make legitimate money by selling encrypted phones to criminals. And he apparently did so. As several of the stories quoted above state, The Penguin sold these phones to members of the Sinaloa and Medellín cartels as well as the Bandidos biker gang in what must have been somewhat of a parallel operation to the recently busted EncroChat devices. X. and his programmers apparently helped develop these phones. The Penguin’s retirement plan also reportedly presented X. with a solution to one of his own problems: The bunker operations were way too expensive and his hosting operation was barely bringing in enough money to cover costs. Nobody in the bunker was getting rich of hosting illicit websites, it seems.

But at some point, the business relationship between the Dutch bunker lover and the Irish crime boss seems to have soured. Green, also known as The Penguin, regularly talked disparagingly about X. in intercepted phone calls. It apparently hadn’t escaped the mobster that the peculiar Dutch internet nerd in his bunker hideout wasn’t the best businessman. Prosecutors are charging X.’s ex-girlfriend B. with having been responsible for keeping the organisation’s books. Most clients paid relatively anonymously by Bitcoin, but the CyberBunker apparently also excepted payment in cash by mail or even dropped off in envelopes at the bunker gate. But they way all of these stories make it sound, there couldn’t have been much money left after expenses for the upkeep of the bunker and the cost of the crew’s extravagant expenses for eating out and visiting nightclubs in Tier.

Maybe this is the reason why Green seems to have disassociated himself from the bunker crew? Or maybe he was tipped off about the German police being onto him? All we know is that he was long gone by the time a group of 650 officers – including members of counter-terrorism units and Germany’s equivalent of SWAT teams – raided the bunker and simultaneously arrested the eight defendants who at the time were eating in a popular local restaurant in Trarbach. It seems the undercover police informant had managed to lure everyone to the restaurant under the pretense that he wanted to celebrate having unexpectedly come into an inheritance. Six additional suspects were also indicted but weren’t in town on that day and, apparently, remain at large.

A Lot of Work for the Prosecution

Even with a confession or two from some of the inhabitants of the bunker – which seem unlikely from X. or his two sons – the team around head prosecutor Jörg Angerer has a lot of work ahead of them. Before they can even start to prove that the people in the bunker were running a criminal organisation, which implies the defendants knew what was hosted on their servers, the prosecutors need to prove that crimes themselves took place.

They intend to do this by charging the defendants with seven individual clusters of offences. The first four of those concern underground marketplaces that CyberBunker hosted: Cannabis Road and Wall Street Market were two of the biggest online marketplaces for drugs of their time. The bunker also hosted Fraudsters, an underground forum that was frequented by criminals trafficking malware, counterfeit official documents, fake money, stolen passwords and online accounts as well as drugs. Last but not least, the prosecutors say the defendants’ infrastructure hosted the Swedish drug marketplace Flugsvamp 2.0 which, according to Swedish police, was responsible for more than 90% of all illegal drug sales in Sweden at the time. The fifth offence cluster concerns a number of websites that sold new designer drugs imported into Germany in bulk from labs in China. These sites were also hosted in Traben-Trarbach. The sixth offense concerns hosting a search engine that provided links to Tor hidden services that hosted forums for child pornography, illegal Bitcoin lotteries, weapon sales and murders for hire. And finally, the defendants are accused of having hosted the six command and control servers of Mirai, the first large IoT botnet that, as a side-effect of a failed attack in 2016, took down 1.2 million routers of Germany’s largest internet service provider Deutsche Telekom  – which caused €2.83 million in damages.

– which caused €2.83 million in damages.

Defendant X. being led into the courtroom in Trier (Photo: Mario Zender / WochenSpiegel)

After the prosecutors have proven a number of individual cases tied to all seven of these offence clusters, which will take a while, they will move on to show that the defendants knew what was being hosted on their servers and that they actively facilitated their clients’ illegal activities instead of stopping it or cooperating with authorities. The prosecution will most likely do this by going through the trove of internal emails they seized when they confiscated all the servers, including the email system. Amazingly, most of the data on these systems was unencrypted. When I asked Angerer why he thinks that was, he said: “I really don’t know. I guess they felt secure enough in their bunker?” He also reiterated that, to this day, investigators haven’t found a single legit, above-board client among the more than 2 petabytes of data they seized.

The Rule of Law in Cyberspace Might Be at Stake

The lawsuit is set to be a long and hard-fought one. X. seems to be intend on maintaining his innocence. His defence seems to be that he didn’t know what was on his servers and didn’t want to know. He compares his hosting company to a bank, which also has no business in knowing what its customers store in their safe deposit boxes. The prosecutors on the other side will be intend to get as many convictions as possible. They can’t afford to have this landmark case go wrong. If they are not able to convince the judge that the defendants ran a criminal enterprise and knowingly cooperated with clients they knew to be involved in criminal activity, the case will most likely set a dangerous precedent for legal proceedings against hosting companies in the future. It will become a lot harder for prosecutors and police to obtain wide-ranging warrants to surveil such suspects. Which might severely impede the investigation against the next bullet-proof hoster of choice for criminals looking to sell drugs or fraudulent documents.

Having possession of the internal, unencrypted email server gives the prosecution a lot to work with. They stated in the indictment that they have clear evidence of how the CyberBunker crew reacted to reports of illegal sites being hosted on their infrastructure: Instead of taking the sites down, they generally forwarded these reports to their clients. And in some cases they even offered to help them stay online by selling them (for an added charge) something they called “stealth service”. So far it hasn’t been made clear in technical terms what they actually did if you ordered that service, but they did offer it to the client who ran the Mirai botnet to escape the blacklisting of his C&C servers by an anti-spam service. There is also some evidence that will most likely weaken the prosecution’s points, however. There are records of the hosting company in the bunker readily complying with federal police officers when these turned up to seize the servers of the underground site Wall Street Market. So it is evident that the bunker crew did comply with authorities in some cases. It also seems questionable that massive surveillance of the suspects was authorised based on the presence of The Penguin in Traben-Trarbach, but the Irish gangster was then never indicted. I wonder if the defence will argue that this means that the raid on the server farm was unjustified and that evidence was obtained illegally.

However the judge decides, it is likely that there will be appeals, so this story might be with us for a long time. I intend to follow it all the way, because it is a very peculiar one from start to finish. A story that involves crazy characters and far-fetched settings like picturesque German country towns in the middle of nowhere and old nuclear bunkers. Who in their right mind would even get the idea to run a datacentre for illegal websites in a place like Germany, instead of somewhere with authorities that can be more easily bribed or browbeat? I mean …come on!

I will keep you updated on where this fascinating story leads. Either by providing you with links to my writing on this in other places, or if nobody wants to hire me to do this, right here on the blog.