A Walk in Gemini Space

Want to try something new? How about an alternative protocol to put sites on the Internet, completely separate from the World Wide Web as we know it?

Photo by James McDivitt, Gemini IV

Most people equate the Internet with the World Wide Web (WWW). That is, they think the world-spanning network of computers that was originally developed by the US Department of Defense is the same as the collection of websites served over that network using the HTTP protocol. In fact, there are other protocols that can be used to serve websites on the Internet that are not part of the WWW and do not use HTTP.

One such protocol is Gopher and there are, in fact, still Gopher servers out there. Even though there is a small, but dedicated userbase for Gopher, I’ve never really developed any interest in it. Probably because it can’t be seen as an alternative to the web and also because I’ve never been a fan of the subculture that uses it. Still, the idea of alternative website protocols has always intrigued me. After all, the web – with all its power and mass of information – is a security and privacy nightmare. And I’ve always had sympathy for the underdog, too. The idea of a tiny space of websites, openly accessible, but hidden from prying eyes by virtue of the obscurity of its technology, has a certain appeal to me.

That’s why I was very excited when I recently found a blog post titled Discovering the Gemini protocol by Sylvain Durand. It turns out that there’s a new Internet protocol I’d never heard of. Gemini (named after NASA’s in-between spaceflight program) is designed to occupy a space between Gopher and the Web. Not quite as sparse as the text-only Gopher, but also much, much lighter than HTTP. Gemini, by design, is not extensible. It has no provision for images, videos, text formatting, state-tracking or scripts.

Gemini websites (called “capsules”) are Markdown-like text pages that support no inline formatting or links. All you have is normal text, headings, blockquotes and links separated on their own lines. Paragraphs are written as continuous lines and the author has no control over text flow. Gemini is specifically designed so that the client alone decides how pages are presented (including layout and fonts). Which makes writing them very puritan and helps accessibility. It also brings with it an incredible focus on the actual content – a strong sense of function over form.

Gemini is TLS-encrypted by default and because it is not extensible, there is no way for servers to track users beyond their page requests. For somebody who’s been talking at length about the privacy challenges inherent in the modern Web, this is a very exciting concept. Of course, Gemini will never replace the web and it isn’t meant to. But the idea appeals to me very much – maybe exactly because it isn’t meant as a replacement. In fact, I’m just going to quote what Sylvain wrote in his blog post, because I think it is spot on:

I miss the web of 20 years ago: simpler, open, where you used to browse directories to find some small websites, often made by passionate amateurs. All the content was available, there were no barriers, no social networks, no tracking. The pages did not exceed a few tens of kilobytes.

Above all, we used to meet people there: small personal sites, forums and IRC chats were meeting places where one could share and exchange a lot of things.

Internet has been privatized. The small web still exists, but is buried and hardly appears in search engines anymore. There is more content and people than ever before, and yet one quickly locks oneself into the same routines and circles. Web languages have become so complex that building a new browser has become impossible. We have built an oligopoly.

Gemini takes the daring step of starting from scratch: rather than starting from scratch with HTTP and HTML, it reinvents them, in a deliberately minimalist and non-extensible way.

I started on the Web relatively late, in 1998, but was still early enough to experience a largely indie-centric collection of websites free of corporate influence. Private citizens creating content for content’s sake or because they were having fun with it, not to make money. I also miss those days. Since making money off something so spartan as Gemini will be extremely challenging, I hope it can become the new enclave of the currently very much buried indieweb. If it will ever take off. Who knows? There are definitely not that many pages out there yet: ⇒ According to the geminispace.info search engine there are currently only 235,304 documents on a mere 891 domains being served via Gemini.

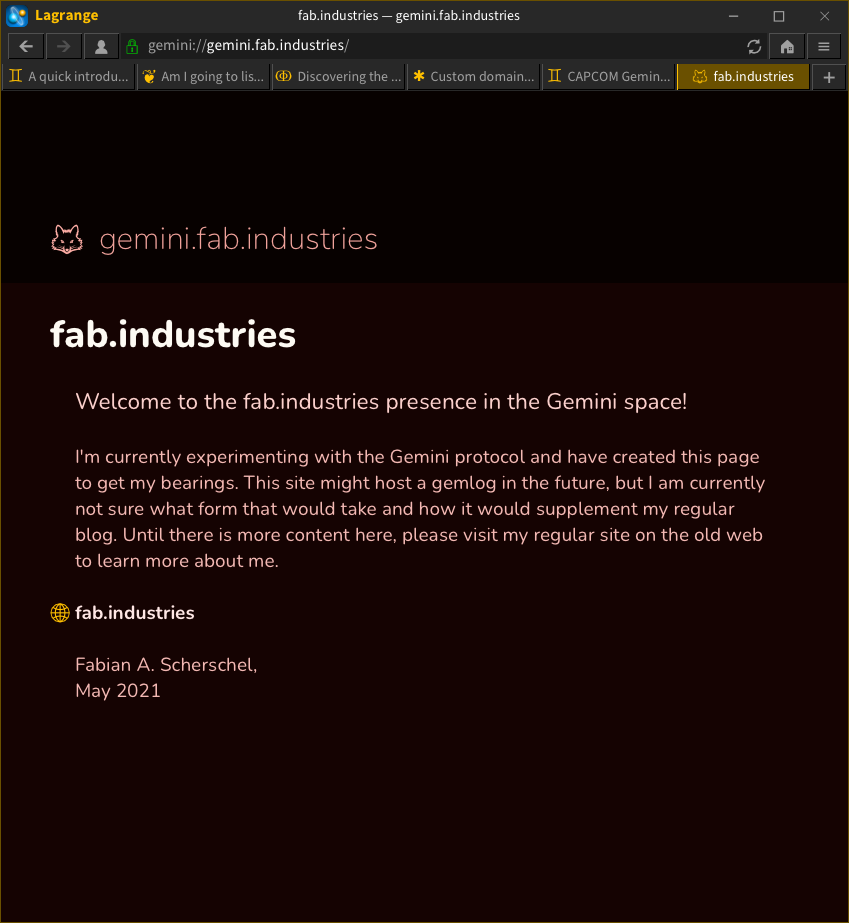

Popular or not, it has been a lot of fun to play around with this new protocol. I’ve been busy reading around the Gemini space, using the Lagrange GUI client on Windows and the Amfora terminal client on Linux. Since no current web browsers support gemini://, you have to use a standalone client at the moment. On the upside, Gemini’s text-only format is excellently suited to be used on the command line. Therefore, it works brilliantly over an SSH session, too.

As an experiment, I’ve even set up my own Gemini site at ⇒ gemini.fab.industries. For the moment, it’s hosted by a third party server via sourcehut and there’s not much on there yet, but I might turn it into a lightweight blog in the Gemini space (a so-called gemlog) in the future. I like the minimalist approach engendered by this protocol and the idea of actually handcrafting those pages. I’ve always been fascinated by typecasting and I think I would approach a gemlog with a similar frame of mind. But don’t worry, I would of course mirror that content here on the blog as well, to have it accessible to a wider audience on the Web.

I can’t wait to see how Gemini develops and if it will actually take off. It’s weird and quirky and a massive underdog compared to the Web and I think that is very exciting. I just hope it won’t take off too much, because it being so obscure is very much part of its charm for me.