Coronavirus

The mainstream media is whipping up a frenzy over the coronavirus outbreak that started in Wuhan, China. But should we panic? And how much? How do viruses actually work anyway?

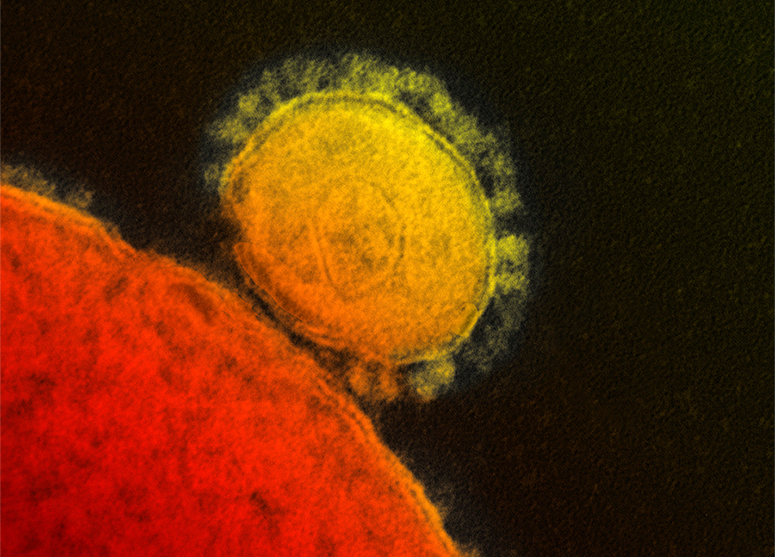

TEM image of MERS coronavirus attached to a cell (National Institutes of Health)

I once read, can’t quite remember where, that humans are very poorly suited to assessing risks in our modern society. This is because we are still hardwired to hunt and gather on the steppes and all our built-in risk assessment is based on figuring out which plants are deadly to us and when to best run away from an animal. This is once again clearly exemplified by the public’s response to the current coronavirus (CoV) outbreak.

While influenza kills up to 60,000 people a year and the measles kill more than 100,000, we prefer to concentrate on this new thing. Because it is exciting and you can scare people with it, which means they will click on your articles. Do you know what the leading cause of death is worldwide? Heart disease. You are exponentially more likely to keel over from a defective ticker than a coronavirus infection this year. If you get a virus, it’ll probably be influenza – seeing as we are in the middle of flu season right now. And that’ll probably be as bad, or benign, as getting CoV.

But to understand how deadly or not coronavirus is, it’s worth understanding what a virus does to your body. If you ever had the actual flu (many people confuse bad cases of the common cold with it, though), you know that it doesn’t feel very good but it generally won’t kill you if you are relatively healthy.

How a Virus Works

Here’s how viruses like this generally work. They are essentially very small particles, much smaller than bacteria or your cells, that in these cases enter your body through inhalation of vapours in which they are contained. They usually have some mechanisms on their outer hull, so to speak, to evade or confuse the body’s immune cells once they’ve entered your bloodstream. They also have mechanisms to trick cells into letting them pass through their outer membranes. Once inside the cell, they basically hijack the cells machinery to produce many many more viruses. This usually ends in the cell bursting.

This happens a lot and at some point you begin to feel sick, because the cells in your body aren’t doing what they are supposed to be doing and are also dying. Somewhere along this process, your immune system will start to generate immune cells especially tailored to removing these virus particles from your bloodstream. This process is faster if you were already expose to the virus in the past – that’s how vaccination works; the vaccine basically fakes a previous infection. At this point a race starts where the virus reproduces more and more and your immune system tries to catch up. With most viruses – a notable exception being haemorrhagic fevers like Ebola – a healthy immune system will eventually win in almost all cases. Haemorrhagic fevers are very deadly, but have the problem that they are too deadly: They kill too effectively and too fast to be spread far and wide. The longer a virus lies dormant (without symptoms) with a host already being infectious to other people, the better and faster a virus spreads.

Viruses usually don’t kill you directly. Most deaths from viruses like influenza, and from what we know of coronavirus it is similar in this respect, occur in patients who already have a weak immune system. Children, pregnant women, the elderly and people who take immunosuppressant drugs (because of existent illnesses) are the ones at risk. In these cases, the immune system is already too weak to keep the virus in check which can cause all kinds of other infectious microbes to suddenly wreak havoc because the immune response is already overwhelmed. Often the actual life-threatening illness is caused by bacteria in a secondary infection. Sometimes the virus itself infects organs such as the lungs and causes pneumonia or other complications.

The problem with viruses is that you can’t treat the cause directly. Antibiotics only work against bacteria. The usual treatment is to give antiviral drugs that generally try to hamper the reproduction of viruses in certain ways. But this only works if the drugs are administered very early on. The idea is to give your immune system a leg up in the race against the virus. The best treatment is prevention, and of course vaccination before you are even exposed to the virus, but because viruses change much more rapidly than bacteria or other microbes, existent vaccines might not work for new strains.

Press Coverage of 2019-nCov

Now the thing about this new coronavirus is that we don’t know that much about it yet. There’s been quite a bit of research done on Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) and Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), which are from the same virus family, but there are a lot of gaps in the data because these are relatively new diseases.

The mortality rates cited in the mainstream media are especially suspect. If you read some of the primary sources, you will see that they are very cautious about this. That is because mortality is generally measured against people who have been infected by the disease, not those who have been hospitalised for it. This includes people who get infected and show no symptoms as well as those who confuse the symptoms with those of the common cold or even the flu and will never seek the help of health professionals. These people are not in the dataset and their numbers can only be estimated. If you read epidemiologic research about influenza, you will notice that it is speculative even there. And we have decades and decades of very good data on influenza epidemics.

In the case of the current coronavirus (2019-nCov), throwing around mortality rates seems very cavalier to me as even doctors on the ground can only base these on hospitalised patients. And with about 5,000 cases so far, the data is mighty thin to draw conclusions in my opinion. From what I’ve read, coronavirus seems comparable to a very bad case of influenza. It might spread more easily, but there’s some argument that this is down to the crowded conditions and overextended healthcare system in the region were the virus first spread. I don’t think there is reason to panic. If you feel sick, go to a doctor, basically. But that always applies.

I’m dismayed to see how this is being reported. The coverage seems to be in absolutely no proportion to the health risk as compared to other illnesses. There is definitely a good reason to report it so that people are aware that the virus exists and what the symptoms are. But the current breathless coverage of every single case is absolutely idiotic. I shouldn’t be surprised though. I know the people reporting on these things, some even personally. You gotta keep in mind that these are people with generally no previous experience in the field they are writing about. They trust other journalists and their usual sources and if they are very, very lucky, they even get half an hour for some basic research. Nobody of these people reads primary sources – they simply don’t have the time. And if they did, they wouldn’t know how to read them and how to weigh them against each other.

People are simply very poorly suited to judging risks in our modern society.

Update: I’ve written a further blog post that summarises some new information on this topic.