NATO Expansion and Putin's War in Ukraine

The Russian attack on Ukraine is a direct response to NATO's post-Cold War strategy of undoing the Russian sphere of influence in Eastern Europe.

“Napoleon in burning Moscow”, painting by Albrecht Adam showing Napoleon watching an abandoned Moscow set alight by the fleeing defenders in 1812

Historically, Russia has always had a pressing need to prevent enemies from encroaching on its borders. This seems to result from the perceived proximity of both of its erstwhile and current capitals, St. Petersburg and Moscow, to neighbouring countries. Russia is an enormous state that straddles two continents, but its capitals have historically always been very close, geographically as well as spiritually, to Europe and tied to European geopolitics. Especially the latter capital, Moscow, has sustained the trauma of attack from without. Both the capture of the city by Napoleon and Hitler’s attempted assault left the Russians with an innate fear of an invasion conquering the heart of their motherland.

This fear compelled Lenin to create a buffer zone around the Russian heartland. When founding the Soviet Union, countries like Ukraine and Belarus were allowed status as semi-independent republics as part of the Union structure. This extended the Russian sphere of influence westwards without overtly annexing these territories and causing nationalist unrest and antagonising the local population too much. This strategy of creating a buffer between Russia and the West was validated by Stalin’s experience during the Second World War and Hitler’s surprise assault on Russia. Stalin was actively working to further expand this buffer both before and after the war.

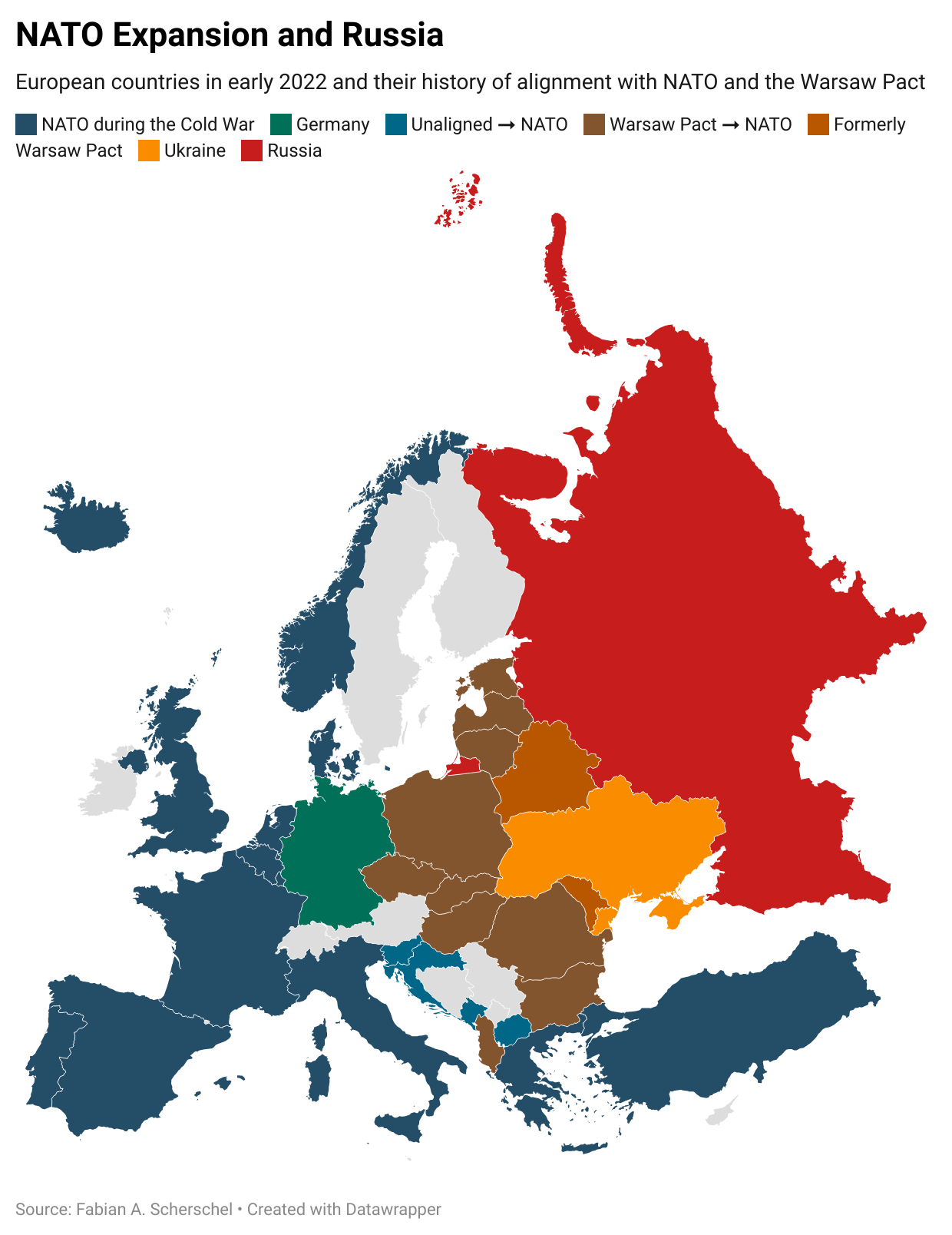

When West Germany joined NATO with the 1955 Paris Accords, the Russians responded by creating the Warsaw Pact — a rival military alliance that also constituted a second ring of buffer countries around the USSR, including Poland. The Soviets’ need for security was so great, that they even built a wall in divided Berlin and erected a political system that came to be known as the Iron Curtain to deter encroachment by the Western powers. This established the geopolitical status quo in Europe during the Cold War, which lasted roughly thirty years. Effectively, Russia’s western border — or at least its practical sphere of influence — was now dividing Germany and continued south from there along the western borders of what is now the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria. During the Cold War, Ukraine wasn’t even the most western extend of Russian political influence, it was further buffered by another row of satellite states to the west.

Geopolitical Defence-in-Depth

This is the era that Vladimir Putin grew up in. Putin lived and worked as a KGB agent in the socialist part of Germany from 1985 until the fall of the Soviet Union in 1990. As a Chekist, he was steeped in a culture obsessed with an almost pathological need to secure the Russian state against invasion — of both physical and ideological nature. As part of his KGB training, Putin was certainly spoon-fed the same doctrine, of reinforcing Russia’s security through a military and political sphere of influence exerted over its neighbour states, that goes straight back to Lenin and Stalin and the Bolshevik security apparatus. A kind of geopolitical defence-in-depth strategy that they developed into almost an art-form.

NATO, on the other hand, has always been less about creating a unified frontline in Europe and more about drawing like-minded countries into a collective security bubble — attack one of us, all of us fight back. Its alliance is less about territory and more about like-minded political views and ideological influence. But with drawing countries into your ideological and economic orbit — and removing them from your opponent’s influence — also come territorial gains. Or at least it looks that way to your enemy. And this, aside from the purely historic enmity, is where the post-Cold War conflict between NATO and Russia is rooted.

NATO’s Eastern Expansion

After the Cold War ended, there has been a continuing effort on the part of NATO, led mostly by the US but also welcomed by many European countries, to reduce the Russian sphere of influence in Europe. Making the Baltic States — Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania — part of NATO in 2004 was less about gaining valuable strategic partners and more about denying Russia influence over these countries. After all, NATO was never about creating a buffer zone made up of expendable allies. So why even expand the alliance eastwards? It was an obvious power grab, a way to minimise Russian influence in Europe.

It is obvious why the Baltic States, and countries like Poland, the Czech Republic and Bulgaria wanted to join NATO and be free of Russian influence and political meddling as part of a more liberal EU-aligned community under NATO. But from the perspective of NATO, what was really gained by this expansion? Political and economical influence over a whole host of countries that, during the Cold War, were in the iron grip of the communists. What the West completely ignored in these expansionist moves was how the Russians felt about the situation.

Ted Galen Carpenter makes a good point when he writes:

“History will show that Washington’s treatment of Russia in the decades following the demise of the Soviet Union was a policy blunder of epic proportions. It was entirely predictable that NATO expansion would ultimately lead to a tragic, perhaps violent, breach of relations with Moscow. Perceptive analysts warned of the likely consequences, but those warnings went unheeded. We are now paying the price for the U.S. foreign policy establishment’s myopia and arrogance.”

As he also points out, the Russians disbanded the Warsaw Pact. Why wasn’t NATO disbanded? What is it protecting against? A valid question, especially from the point of view of Russia.

NATO is clearly still a geopolitical alliance aimed against Russia, a country that in its size and military strength dwarfs any other nation in Europe. The EU could have taken up the mantle of creating a military alliance to counterbalance Russia, but since the US obviously did not want to give up control in Europe, it kept the European defence against the eastern juggernaut centred on itself. And in its short-sightedness and historical arrogance has now manoeuvred Europe into the first shooting war since the unholy mess in the Balkans ended in 2001.

Euromaidan’s Long Shadow

The invasion of Ukraine is obviously very different from the war that destroyed Yugoslavia, first and foremost because it wasn’t rooted in a civil war but an obvious Machiavellian conquest of a neighbouring country. It is Vladimir Putin’s war and starting it is his responsibility alone. But wait a minute… Wasn’t it also a direct consequence of severe internal political divisions within a country? This war did not start on the early morning of 24 February, nor did it come at all unexpected. This war started with the Euromaidan protests of 2014 — now often termed “the Revolution of Dignity” in the West, an obvious propaganda term if I ever heard one — and Putin’s subsequent annexation of Crimea.

A pro-Russian government in Ukraine was toppled, with obvious involvement by the West, and the Russians saw the writing on the wall: they were going to lose Ukraine, and possibly Belarus, to NATO and the EU. And so they reacted, using separatist movements in Eastern Ukraine as a flimsy excuse to send thinly disguised troops into the country and seize Crimea. This was a clear message to NATO to finally stop its expansion and leave Ukraine and the Russian sphere of influence alone. A message that couldn’t have been clearer and one that started this war. Incredibly, it was still mostly ignored by those in charge. The only time the public in the West momentarily noticed there even was a war going on was when the rebels downed Malaysia Airlines Flight 17 in Donetsk.

It is understandable that people in Ukraine want their country to join the EU and NATO. But the way the West and pro-Western Ukrainians went about this was naïve (or possibly reckless) and dangerous. It ignored basic tenets of power politics and forced Russia to react.

Is Putin’s War Also Russia’s War?

It would be as naïve to assume that this war is only in Vladimir Putin’s interests. Russia is an incredibly vast and diverse nation. Just from looking at Russia’s more recent history, it is conceivable that there could be widespread support of Putin’s war. One big factor is the aforementioned need for security. Another is the Russian nationalist spirit, which is very strong and a phenomenon that simply isn’t understood by most Western observers. Especially in Germany, where even having a nationalist spirit is almost inconceivable for most — even leading politicians dealing with foreign policy. A consequence of a rigorous de-Nazification by the Allies after the Second World War and a resulting generational political shift in the country’s population that also severely influenced the education system and thus further generations.1

The situation in Russia stands in sharp contrast to this: The war crimes committed by the Red Army in the Second World War and the atrocities perpetuated by Stalin are largely ignored and negated by the propaganda of a righteous “Great Patriotic War” against Nazi Germany. Why would anyone expect a country, which hasn’t even come to terms with Stalin’s mass murder and the country’s war crimes from a war that ended more than 70 years ago, to deal with the realities of today’s war with open eyes?

Especially since the Russian population is clearly living under a propaganda onslaught that goes as far as denying that the invasion — termed the “Special Operation in Donbass” in Russian media — is even a war. I therefore find it hard to believe that, even though Putin alone is responsible for initiating this war, everyone else in Russia is against it.

Putin’s Pan-Slavic Empire

It also seems unlikely, given the geopolitical situation that has led to this war, that Putin started it because he wants to restore the Soviet Union. Or, even more absurd, that he’s out to create a pan-slavic empire of some kind. There simply isn’t any concrete evidence in his actions that would support such a hypothesis. His proposed “Eurasian Union” is more of an economic bloc than a recreation of the Soviet Union. And an economic bloc to rival the EU and China makes a lot of sense from a Russian perspective. But there seems to be a general fear in the West that the Russian governments utter disdain for the concept of Ukraine as a country is rooted in some kind of wish for a re-establishment of the USSR, when it actually makes a lot more sense that it’s the previously explained reaction to NATO’s encroachment eastwards. If anything, Putin wants the USSR’s buffer states back.

He tried getting that done with softer political meddling in Ukraine and when it failed, and the West also got involved and eventually pushed for regime change, he escalated. And with the invasion, he has further escalated in response to the West not backing down. But even with this invasion, he’s most likely not trying to turn Ukraine into a Russian province, because even the Soviets never tried this. He doesn’t care who governs Ukraine, as long as it is his puppet state and geopolitical bulwark on his western flank.

The idea of a Stalinesque Putin who wants to recreate the Soviet Union, or even worse the Empire of the Tsars, feels like the Western example of war propaganda at work. Similarly, any suggestion that NATO and some EU governments have had a significant part in the situation leading to this war is immediately shouted down in Western media. As the old adage goes: The first casualty in any war is the truth.

There’s Always Two Sides to Every Story

The horrible war raging in Ukraine at the moment was started by Putin and the blame falls to him and his government. But it would be extremely short-sighted, and dangerous, for NATO and its allies to ignore how we got to a point where Putin even considered such a step. The EU was about to acquiesce to Ukrainian demands for membership, even though the Union had massive problems of its own — a string of secessionary movements awoken by Brexit, massive economic problems among its members and fundamental disagreement about how to deal with refugees from Syria and other areas — that should have been solved before loading itself up with even more political and economic burdens. And NATO was ready to pry Ukraine from the Russian sphere of influence even though that would have been a political move with zero strategic or even tactical advantages. A move that makes no sense at all for a military alliance, aside from pure lust for power and influence over countries that once belonged to its biggest enemy.

In short: Western strategy in Ukraine risked much without any tangible benefits, aside from — being hopped-up on its own propaganda — feeling like it was the best for the people, justice and order in Europe. In reality it has resulted in war, destabilised the continent politically and caused untold suffering. And we’ve only seen the beginning of the consequences of these decisions. Whereas Russia reacted, albeit ruthlessly, in a very predictable manner, driven by obvious needs of geopolitics. The West ignored the long-established Russian need for the security of its borders at its own peril and the population of Ukraine is paying the price. And in all of this, it is entirely beside the point whether Putin is mad or evil, if Ukrainians have a right for political and national independence or whether the described Russian pathology about their country’s security is in any way, shape or form justified.

Those who ignore history, notwithstanding their reasoning, are doomed to repeat it.

Listen to this article narrated in my own voice:

This is an archived issue of my newsletter Realpolitik. If you want to receive new issues immediately and directly to your inbox, you can sign up for it here. Subscribe to audio versions of the articles as a podcast with this RSS feed.

-

I am less sure why Americans seem to constantly underestimate Russian nationalism. They certainly got a good taste of it during the Cold War and immortalised it in countless Hollywood movies. And they, of all people, should understand what they usually call “patriotism”. But I guess only the good guys have that? And after all, the Russians lost the Cold War. Why should they be proud? ↩︎